Introducing Stage Viewer: A Simple Visualization Tool Built with SvelteKit and Tailwind CSS

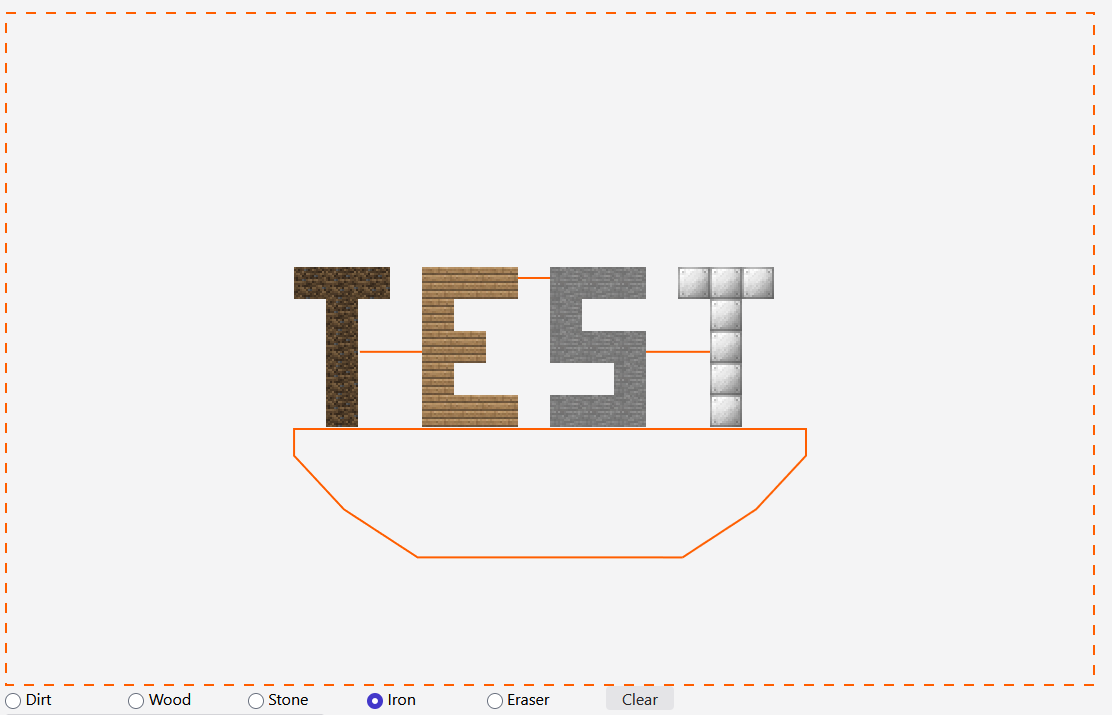

Recently, to fulfill a request from a friend and improve my web development skills, I’ve been working on a project I’ve been uncreatively calling Stage Viewer. The tool helps users visualize and share structures built by the character Steve from Minecraft in the game Super Smash Bros. Ultimate for the Nintendo Switch. Briefly, Minecraft is a game about surviving and building in a three-dimensional world made mostly of cubes, and Super Smash Bros. Ultimate (SSBU) is a two-dimensional fighting game in which the objective is to launch one’s opponent outside of the play area. It features characters from many Nintendo franchises and characters from some third-party video game franchises. In SSBU, Steve can build using several types of blocks, and the creations are aligned to an absolute grid, which corresponds to the current arena, called a stage. This building ability is unique, and it’s essential to high-level Steve gameplay because Steve excels when controlling an opponent’s approach with a structure tailored to that opponent’s particular abilities and movement options. Because the blocks are aligned to a unique global grid for each stage, creating a game-accurate visualization of a valid creation in standard image-editing software is rather tedious. My project aims to solve this problem.

Capabilities

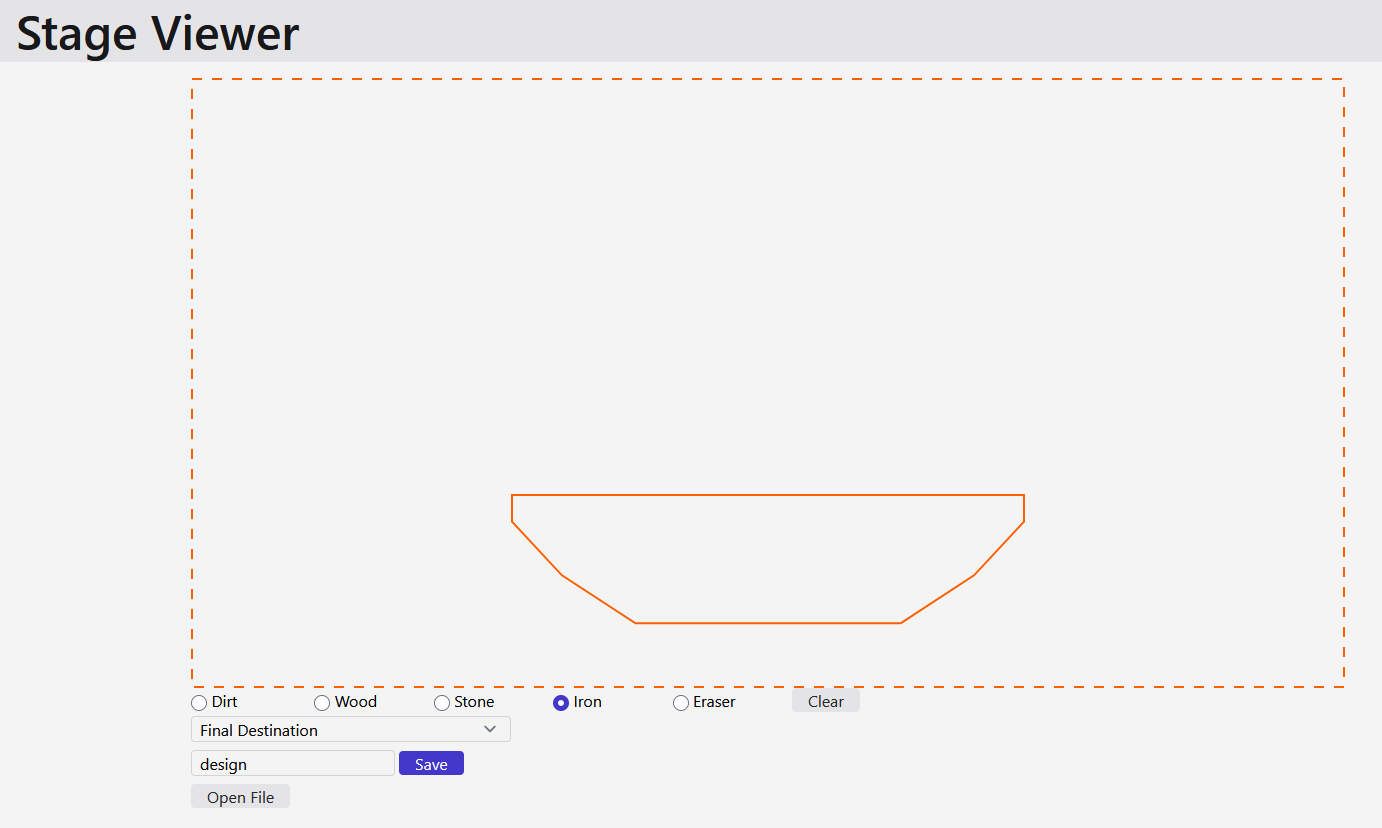

Stage Viewer’s primary purpose is to allow users to create and share game-accurate visualizations of block structures created while playing Steve. Its capabilities support this purpose. The most central piece of functionality is grid-aligned block placement. The application contains a JSON file which includes the information necessary to align the blocks placed by a user to a particular stage’s grid. Essentially, each stage image’s entry includes a map of which grid squares allow block placement and empirical measurements necessary to align this map to the stage image. This system allows users to easily place blocks aligned to the grid, and can be extended to additional stages relatively quickly, by taking a few measurements in a program such as GIMP.

I’ve added two stages so far, and users can switch between them as they like. There are different materials available on different stages, and infrastructure is in place to support swapping out materials accordingly. There is an erase tool and a clear button. The HTML canvas is the main representation of the creation presented to the user, but the ultimate source of truth is a JSON representation of the locations blocks have been placed. JSON representations of creations can be saved as files and loaded from files, enabling size-efficient and portable representation of creations.

Future Plans

Full Tauri support is my immediate next priority, since my final intention is for the app to run locally in order to alleviate web hosting demands. I also plan to enable easy image downloads and add the remaining popular competitive stages. In the longer-term, I plan to overhaul the canvas system to add an overlay representing the block placement grid, use SVGs for the stage background, dynamically scale the canvas to clean resolution multiples, and refine the app’s overall appearance.

Additional Information

You can check out Stage Viewer’s code at its GitHub page. I may soon write a post covering some of its more interesting technical aspects. I’ll continue updating the software to implement the plans I discussed above. I’m not sure yet whether those expansions will warrant posts on this blog, but I will also be posting about other topics and projects here.

Credits

This project uses stage images created by Tournameta’s Stage Comparison Tool, used with permission. The block textures are from the Coterie Craft texture pack, which is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.